|

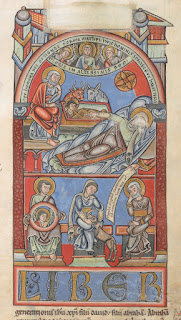

| The Nativity of Christ, from the Floreffe Bible, British Library, Add MS 17738, fol. 168r (ca. 1170, Belgium) |

From the Speculum Ecclesiae of Honorius Augustodunensis (early 12th cen.)[1]

Let the heavens be glad and let the earth rejoice! Let the mountains break into songs of praise, for the Lord has comforted his people and will have mercy on his poor (Ps 95[96].11 / Is 49.13).[2] It is right that the heavens are bid to be glad today, for today they have gained the illumination of new light and new joy. Today indeed heavens’ King has willed to visit the earth with his presence and to restore through humans the loss incurred in heaven by the angels’ fall.[3] So at once the heavens have shown their cheerful joy to the world by sending forth a shining star in honor for their King. It is also right to urge the earth to rejoice today, for the Truth that sprung up from the earth (Ps 84.12[85.11]) has come today to free her from the curse and to unite humankind, born from the earth, with the angels in heaven. The earth has made her great exultation known to the world today by pouring forth from her womb a spring of oil for her God, who is born from her bosom, and offering it to those who look in wonder [4] The mountains, too, are urged to break into song in praise of God.[5] The mountains are the patriarchs and prophets, who transcended human merits by their holy way of life like mountains that rose high above the plains of the earth. Today they have broken into song in praise of God, for what the patriarchs once foretold in figures and the prophets in Scripture, they rejoice today to see fulfilled—that the people of the Gentiles who walked in the darkness of ignorance have seen today the great light of God’s eternal Wisdom (Is 9.2). And on those who dwell in the land of the shadow of death—that is, hell—light has risen (Is 9.2): Christ is born, the splendor of the everlasting Father;[6] after coming down for them and snatching them from the darkness, he drew them towards eternal light.